Many lists of great minor noir movies includes the 1952 train-centered The Narrow Margin, where a tough cop from LA is sent to Chicago to secretly escort a mob moll, Mrs. Frankie Neal, back by train so she can testify against her husband's gang. Gangsters get on the train to find her and kill her. The movie is usually described as tight and suspenseful, and, at 71 minutes, goes by fast.

Still, I think it is overrated, for reasons I will go into. People really like it for one thing: the performance of Marie Windsor as the moll.

"You don't like me--but you aren't going to look anywhere else."

"You don't like me--but you aren't going to look anywhere else."

You may remember her as the disastrously sexy Sherry Peatty, the unfaithful wife of the Elisha Cook, Jr. character in Stanley Kubrick's 1956 noir, The Killing:

A classic noir marriageWhat happens in The Killing is mostly her fault (as expected). But what is with the "noir bad girl" wig thing? I mentioned this in my discussion of Too Late for Tears a while ago. Fortunately, the actresses compelled to wear these things were hot enough to overcome their disadvantages.

A classic noir marriageWhat happens in The Killing is mostly her fault (as expected). But what is with the "noir bad girl" wig thing? I mentioned this in my discussion of Too Late for Tears a while ago. Fortunately, the actresses compelled to wear these things were hot enough to overcome their disadvantages.

Fortunately, if Windsor's wearing a wig in The Narrow Margin, it is a good one.

Windsor does her wise-ass sparring with Walter Brown, who is as bricklike as his name, and not much of a sparring partner. He is played by Charles McGraw, who has a voice like a cement mixer. He looks and acts a bit like a slowed-down Kirk Douglas, and, what do you know, he played Douglas's gladiatorial trainer in one of my favorite boyhood movies, Spartacus.

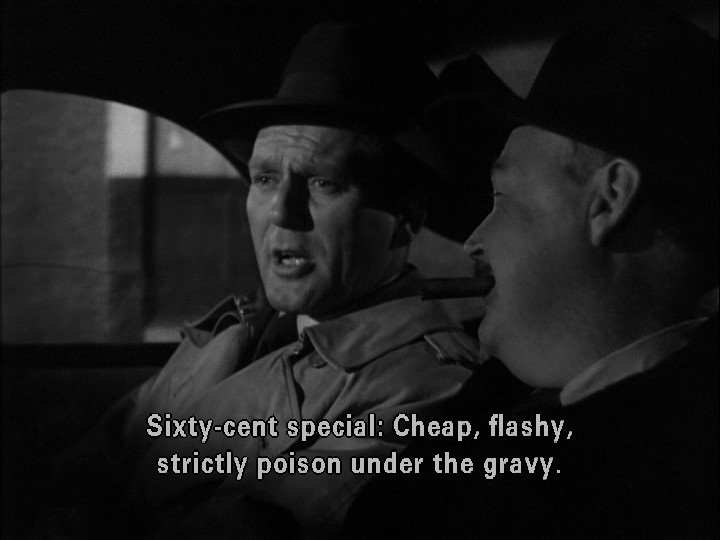

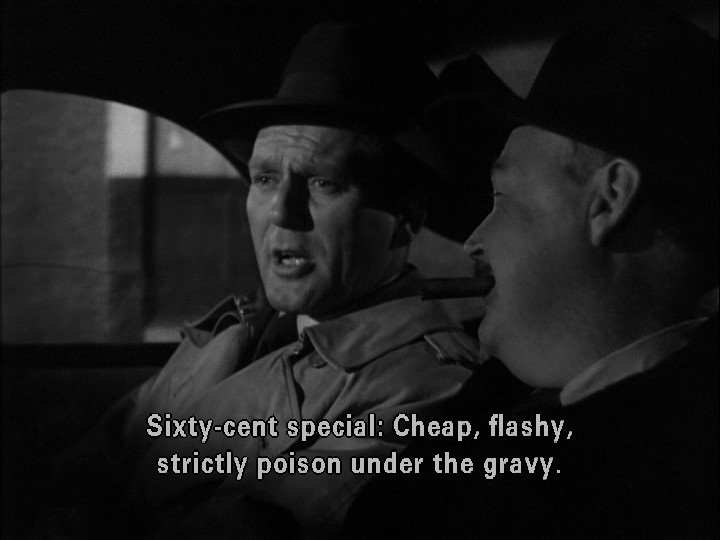

Brown comes to Chicago with his older, wiser, more cynical partner, Gus Forbes, to to pick up Mrs. Neil. En route, Forbes asks Brown what he thinks Neil looks like. "A dish," Brown answers. "What kind of dish?" And then we get this classic description:

Translation: "girls are icky."Because who else would marry a hood? But there is a twist in the plot that brings this whole assumption into question. But that twist is not the one that is interesting.

Translation: "girls are icky."Because who else would marry a hood? But there is a twist in the plot that brings this whole assumption into question. But that twist is not the one that is interesting.

Here at the Chicago apartment, someone is lying is wait, and as Forbes and Brown escort Mrs. Neal out, someone tries to kill her, and kills Forbes instead. Brown gets her safely to the train station, and aboard the train. There she is resentful, and he is angry, sad about his partner, but dedicated to his job. They never do learn to get along:

"I still think you're icky."After this, it's a bunch of hugger mugger, with an innocent woman with one of those annoying 50s children whom Brown befriends, and several overlapping baddies. In fact, one smooth baddy who tries to bribe Brown is then whisked off the train at a station stop and is replaced by another one who flies from Chicago by plane to totally disrupt the "we're all stuck on this narrow train" concept. And, at one point, a car drives parallel to the train on a totally straight road for miles and miles, also messing up the isolation scenario.

"I still think you're icky."After this, it's a bunch of hugger mugger, with an innocent woman with one of those annoying 50s children whom Brown befriends, and several overlapping baddies. In fact, one smooth baddy who tries to bribe Brown is then whisked off the train at a station stop and is replaced by another one who flies from Chicago by plane to totally disrupt the "we're all stuck on this narrow train" concept. And, at one point, a car drives parallel to the train on a totally straight road for miles and miles, also messing up the isolation scenario.

The story is really about institutional corruption, not about Mrs. Neal. Everyone is compromised, particularly Forbes. If this was an actual noir, the events of Forbes's death in that Chicago apartment building would be returned to, a couple of times, as it is reinterpreted.

And Mrs. Neal should actually do manipulative, maybe even nasty things in her desperate attempt to survive. There is actually an explanation in the movie for why she doesn't, but it comes late and is just a routine movie reversal rather than something that makes you reexamine all of your assumptions about what's going on. I do like that Brown never warms to her, never likes her, and never even seems to find her hot, which shows something about him, given the fact that they have to live in such close proximity:

A mysterious man on the wall is standing between them: part of the hidden movie.Forbes was clearly on the take. Someone took him out, or he got taken out by accident. And all the playing around in the train has a deeper purpose. I actually think a lot of this was in the story originally, but was removed during rewrites, or edited out to keep the focus on Windsor, and the running around on the train. Fine, I guess, but it leaves a perfectly good noir plot just sitting around, ready to be reused.

A mysterious man on the wall is standing between them: part of the hidden movie.Forbes was clearly on the take. Someone took him out, or he got taken out by accident. And all the playing around in the train has a deeper purpose. I actually think a lot of this was in the story originally, but was removed during rewrites, or edited out to keep the focus on Windsor, and the running around on the train. Fine, I guess, but it leaves a perfectly good noir plot just sitting around, ready to be reused.

Speaking of "running around", at several points Brown is blocked in the narrow corridor by a self-deprecating fat man, Sam Jennings:

"No one likes a fat man except his grocer and his tailor"

"No one likes a fat man except his grocer and his tailor"

There's something to him, but not enough. Potentially another interesting and expanding character.

Good stuff:

Aside from some credits music, there is only ambient sound in this movie, including the portable record player Mrs. Neal plays her jazz records on.

Brown never falls for Mrs. Neil.

Given the limitations of the big cameras they had then, this has amazingly flexible camera work.

In addition to that lacy thing, Mrs. Neal shows why giving up on dresses has made our lives poorer:

No need for a negligee with a dress like this.Oh, look, her hair does look like a terrible wig here. I think I have uncovered the dark truth of noir.

No need for a negligee with a dress like this.Oh, look, her hair does look like a terrible wig here. I think I have uncovered the dark truth of noir.