Last week's discussion of how to win WWI got me to thinking about how you draw lessons from history--more specifically, in this case, military history. You won a battle. Or you lost one. Why? What about your approach, your weapons, your generalship, was the decisive factor? Deciding this is much harder than historical fiction makes it sound, because the easiest (and laziest) way to make a historical character seem smart is to have them anticipate the future and be able to easily distinguish between the necessary and the contingent in a way that was completely impossible for any real person living in the confusing flow of actual events.

This, incidentally, is how doctors in historical fiction work. They anticipate the past couple of centuries of data analysis, experiment, and many false paths just by being smart and observant, so they never ruthlessly bleed people, blister their heads, or make them throw up, and then blame them for not getting better, unlike real historical doctors. I've never read a credible doctor in a historical or fantasy novel. Stephen Maturin in the Patrick O'Brian books comes closest, I guess, but even he has a too-high success rate.

The entertaining Great Courses class The Decisive Battles of World History, by Professor Gregory Aldrete, starts out with a description of the 1866 Battle of Lissa, in the Third Italian War of Independence. Don't worry if you've never heard of either the battle or the war--I never had either.

Lissa was a sea battle between Italians and Austrians off the coast of Croatia, and involved both ironclads and wooden sailing ships. The Austrians won, but since they lost the significant Battle of Königgrätz (also called Sadowa) to Prussia the next month, this particular victory had little effect (Aldrete uses it to lead off a discussion of what actually makes for a decisive battle). But during the Battle of Lissa itself, several ramming attacks helped decide the issue.

As a result of this, all European navies for the next 40 years put rams on their battleships, as if they were giant, steam-powered triremes (perhaps the example of ancient Greek naval warfare encouraged over-educated procurement officers to make this odd decision), even though they would prove to be utterly useless in an era of long-range gunnery.

Here are a couple of examples. First, the American ship USS Alarm, 1874:

Then there is the HMS Polyphemus, 1882:

It's not just the name: the Polyphemus really did look like a trireme:

During the US Civil War, in 1862, the USS Cumberland was rammed and sunk by the CSS Virginia during the Battle of Hampton Roads, but Europeans tended to neglect the instructive experience of those crude Americans during their internecine squabble. It was Lissa that was influential.

In retrospect this seems completely crazy. But there were real reasons for making this choice. Naval guns were still weak and inaccurate, while armor had already become quite good. So shells tended to be ineffective in sinking opposing vessels. The ram promised a useful form of offense that would even the odds. They never actually ended up being used in battle. And naval guns quickly became more accurate and more powerful.

But these rams were not only useless. According to this Center for International Maritime Security article, they were actively dangerous, because ships on the same side tended to sink each other on maneuvers, or in bad weather. It was running with scissors, naval style. You ended up poking your eye out.

It is incredibly difficult to figure out what is the important fact from a chaotic, fast-paced, and contingent set of experiences. And don't ignore the influence of trends, conventional wisdom, and fear of being wrong or ridiculous.The people who make influential decisions are always embedded in a complex and interactive social matrix. If they aren't, no matter how smart they are, they have no influence over events.

It would be incredibly hard to write a novel where you show a really smart person being repeatedly and completely wrong--and still smart. But that is what history is all about, how truly hard real lessons are to learn.

None of the many ship models I made in my youth was an ironclad with a ram. But now I'd like to find one.

And maybe I can work one into a story somehow.

Are you really sure this is the last time?Of course, this picture is from 2013, the last time Anthony Weiner and Huma Abedin had some technology-enabled marital trouble, not this most recent (and seemingly final) time.

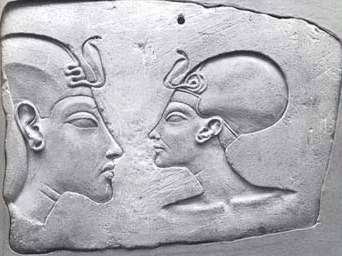

Are you really sure this is the last time?Of course, this picture is from 2013, the last time Anthony Weiner and Huma Abedin had some technology-enabled marital trouble, not this most recent (and seemingly final) time. Instead of playing with monotheism, why don't you run for mayor?That's right, back in the fourteenth century BCE, Akhenaten and Nefertiti ruled Egypt, causing all sorts of trouble. And, odd bit of headgear aside, it looks like they have been reborn roughly 3,450 years later. The resemblance is actually startling.

Instead of playing with monotheism, why don't you run for mayor?That's right, back in the fourteenth century BCE, Akhenaten and Nefertiti ruled Egypt, causing all sorts of trouble. And, odd bit of headgear aside, it looks like they have been reborn roughly 3,450 years later. The resemblance is actually startling.