An Interstellar encounter

Note: there area couple of minor spoilers in here, for those who have not seen the movie. There is a bit of unexpected casting, not listed in the publicity materials, that is a genuine surprise. I'm actually not sure what the point of that surprise is, really, but it is there, so think about it before reading.

Science fiction movies come in two main categories, both large: the loud, weaponized alien invasion type, with stuff blowing up and carefully placed taglines, and the spiritually transcendent Big Idea kind with soaring music and people staring off at things. Chistopher Nolan's recent Interstellar is definitely that second kind.

It was OK, actually. It had some good science fiction stuff in it, though its best parts seemed to crib a bit too much from the 2013 Cuaron film Gravity (a vastly superior work, I think, largely because it was on a human scale, involving the survival of a single person in space, not entire races, civilizations, etc.).

I could go on about a lot of stuff I didn't like in it (the stunt-cast Matt Damon plays a smarmy douchebag so well it is startling than anyone would ever believe a thing he has to say, for example), but I want to focus on just a couple of things: the film's portrayal of poverty, and of dishonesty.

The world we step into in the beginning of the movie is explicitly impoverished. Crops are failing, civlization has largely collapsed. And its intellectual horizons are likewise impoverished, as is shown at a parent/teacher conference where a former astronaut is cautioned to not have his daughter tell her classmates the Moon landings ever really happened--those dreams will impede recovery, it is implied.

But the main character, Cooper, lives with his family in a classic Midwestern farmhouse. He drives a pickup truck, goes to baseball games. It is dusty. OK. But otherwise, it does not look like any real compromises need to be made. Even the corn we see is high and vigorous (though weirdly flammable, as is shown in a late scene that makes little sense).

The whole thing is symbolized when the pickup has a flat. Cooper says to get the spare, his son says "that is the spare". Then a drone flies past and Cooper takes off in pursuit of it. Despite the fact that his rear tire is flat, he drives up and down hills, and through cornfields that, presumably, are the only food they have. The terrain is hillier than good corn country generally is, but I can deal with that. What I can't deal with is that the flat tire vanishes as an issue.

Having a flat you can't easily fix is a great referent for poverty. Nolan likes the idea of poverty, but neither its reality nor its appearance.

Later, of course, we find an entire concealed space program, paid for by some secret appropriation, and one that is much more effective than our own open space program.

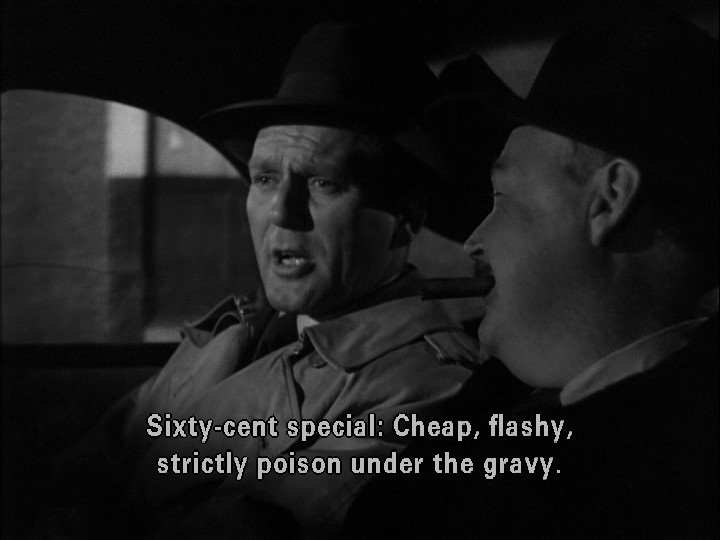

This is all a lie--appropriate, becaue, aside from poverty, the movie is about lies and promises not kept (except by deus ex machina miracle). The government lies to people to keep them from dreaming too high, Cooper gives his daughter an assurance he can't keep, Damon's Dr. Mann lies about his planet, Anne Hathaway's Brand (did she really not get a first name?) lies about how neutral she is about picking the planet that holds her lover (in a self-justifying speech so lame I can't imagine the crew doing multiple takes of it without cracking up), Michael Caine's Dr. Brand lies about pretty much everything.

Some of these lies aren't just self-justifying fibs, they threaten the very survival of the human race. This is a society in crisis, falling apart and losing everything that once held it together. How does an honorable person of good will deal with this situation? That's an interesting movie, and one, I think that the Nolans had in mind before they succumbed, as they usually do, the the lure of their favorite fabrics, fustian and bombast.

And can we give "clever" robots a rest for a while?

I did like a couple of moments:

Cooper and Brand return from serious time dilation on their first planet and the man they left in orbit stares at them, quaking, because for him it has been over twenty years.

Dr. Mann starts on a standard self-justifying villain speech but doesn't get more than three words into it before the consequences of his bad decisions wipe him out.